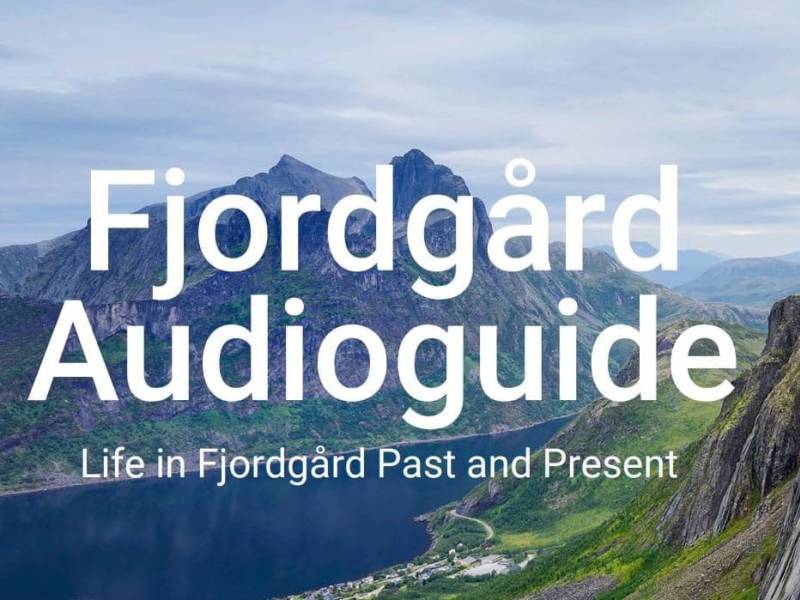

Listen to the story of Fjordgård (Audioguide)

0

Listen WHENEVER and FROM WHEREVER you want. Or take the walk on site; the map in the app shows you where to go. 30 minutes.

0

Listen WHENEVER and FROM WHEREVER you want. Or take the walk on site; the map in the app shows you where to go. 30 minutes.

A very warm welcome to this audioguide in Fjordgård! Our starting point is here at the village’s best viewpoint below the foot of our world-famous mountain, Segla. So, relax and enjoy the beautiful view while I fill you in on how this audioguide works. People have been living here on North Senja for several thousand years, so get ready to find out what some of their lives were like. (We’ll be talking about everything from fisheries, public meetings and steamships to local stores, the danger of landslides and art galleries. Not only that,) You’ll also hear about the time when the entire community’s very existence was at stake. The map on your mobile will show you where to go and I come in automatically when you arrive at the next point of interest. Wander at your own speed. You can put the recordings on pause, wind back or read the text of what I have to say on your screen. Here’s hoping you enjoy the experience! If you now look out over Øyfjorden towards the left, you are looking north. Set sail in that direction at a rate of 40 kilometres per hour and you’ll brush past Svalbard after about 20 hours. Keep going and you’ll be able to set foot on the polar ice-cap after 2 days and nights. Fjordgård lies at the entrance to a fjord arm called Ørnfjorden; Eagle Fjord. If you’re lucky, maybe you’ll catch sight of the local white-tailed sea eagles – they nest on the steep crags over on the other side. The landscape appears as it now does thanks to the work of the sea and, not least, the procession of ice ages. Ice lay thick across the entire island and didn’t melt away until around 12,000 years ago, leaving fjords, valleys and steep mountainsides behind it. All the same, the 500m + mountaintops stood proud of the ice as so-called ‘nunataks’, and were interminably exposed to the wind and weather. In this way, our local mountains gradually attained their spectacular rugged form. The Senja mountains are between 1.7 and 2.8 billion years old and are therefore among the oldest on Earth. From here you can see the highest mountain around the fjord on the far side. Named Keipen, it is 938 metres high. On this side of Keipen is Grytetippen or ‘Cauldron Edge’, and when fog or blizzard set in, the whole formation looks like a gigantic witch’s cauldron in which the gods might boil up one helluva brew. Not too bad to be standing safe down here, is it?

Senja Montessori School is now on the lower side of the road, where the community’s 20 or so children and adolescents receive their education from first to tenth grade. In 1739, it was decided that all Norwegian girls and boys were to have an education. But in Fjordgård, threatening a school strike proved necessary before suitable school premises were built. Before that, pupils were often taught in draughty fishing huts or noisy fish processing facilities. The community got its first school building in 1949 – we ‘inherited’ the former German barracks of the second world war occupation. The building you now see stood ready for students in 1965. The local authority tried on numerous occasions to close the school down and finally succeeded in 2014. Local parents had to enter the fray once more and, thanks to their hard work and determination, we still have a school, now privately run. The most hard-working teachers were undoubtedly those who served their profession in the 19th century. They came to work on foot over the top of the mountain or rowed in from the neighbouring fjords. The most famous teacher the school has ever had is author Karl Ove Knausgård, world renowned for his autobiographical novel called My Struggle. As a later school principal said: “He lived here, he taught here, and it was here he drank his first karsk!” – Moonshine to you and me. Fjordgård is the setting for heated, controversial scenes in a number of his novels but people here think what fun it is that Knausgård numbered among them for a year. The school’s bravest teacher is Sigurd Helsem, who taught here during the Second World War. He refused to accept the nazification of tuition as dictated by the occupying forces and was sent to the internment camp in Kirkenes for his pains. Fortunately he survived the ordeal. Elders villagers remember his as a strict but scrupulously fair teacher. The make-up of the current teaching staff is somewhat of an outlier in modern Norway – there are actually just as many male teachers as their female colleagues. Modern Norway also benefits from the thousand year-old tradition of people working free-of-charge for the common good. Indeed, Norwegian is unique among Scandinavian languages in having a word for this practice; ‘dugnad’ – or ‘dugna(th)r’ as it used to be in viking times. The school is proud to bring this tradition further, and every year the school’s pupils may be found collecting rubbish along the road to ensure that everything is looking its best for the Norwegian national day on the 17th of May. The school pool is open during the winter and, in the spirit of ‘dugnad’, local adults take it in turns to don their swimsuits and assume lifeguard duties. The maintenance of all the community’s shared spaces is also the results of ‘dugnads’. We think the Norwegian ‘dugnad’ is really something to be proud of. Don’t you agree?

Walking down the hill, we can see the most important way of getting to Fjordgård: the sea. Several thousand years have passed since boats first sailed up Øyfjord, and for centuries all contact with the outside world was by boat or on foot – or by letter: Fjordgård got its first post office – ‘the letter house’ – in 1928. Its telephone came 5 years later. Not having a road connection to the outside world proved pretty tough at times. A villager taken seriously ill would be transported out by seaplane. Patients had to be lifted onto a boat, driven out and hoisted on board the seaplane bobbing on the waves. Many a Fjordgårding, moreover, has been helped into the world by the Catholic nuns at the old St. Elisabeth maternity home in Tromsø after a nervous seaplane flight for their expectant mums. There is a good chance, however, that you arrived here by car. If you did, then you’ll have driven through three tunnels. The first, the Ørnfjord tunnel, was completed in 1975. This brought people to the head of the Ørnfjord, from where they could take a ferry to Husøy over the other side, and another from there to here. It was finally possible to drive all the way to Fjordgård from 1979. The road, however, was frightening prone to avalanche and rock fall. Bus drivers refused to drive down to the village, and the local road authorities refused to clear the road of snow on this account. Then, one year, an avalanche closed the road completely. April arrived, and the road remained impassable owing to the heavy masses of snow. Grabbing their spades the Fjordgård villagers managed to level off the snow into a strip which was even then several metres high. The road was thus made just about passable, although you had to fold in your wing mirrors to be able to get through. An arduous struggle to make the road safe continued throughout the eighties. Experts were invited to undertake surveys and public meetings were held. But it was the efforts of the local women’s group – who made a great impression on visiting politicians from the Norwegian parliament – which finally got us the money for a new tunnel. And so the 2.3 kilometre Fjordgård tunnel was finally opened in 1989. It retains the dubious honour of being one of Norway’s worst tunnels, by some simply termed “a disgrace”, while others call it “an intestine with overhead lighting”. Last of all you drove through the Fjordgård pipe tunnel, before you came to the end of the road in our cosy – and now safe – little village. But remember, wherever you come from, you can always use the sea route to the coast nearest your home. There is, after all, no end of the line to the sea.

Behind you now you’ll find Segla Grill & Pub: Fish & Chips a speciality, with a ½ litre to wash it down perhaps. They take overnight guests too. After our popular mountain, Segla, has become famous around the world, tourism has become important as a source of income for a number of Fjordgård inhabitants. Others work as nurses or have office jobs and commute to the municipal centre, Finnsnes, which is an hour’s drive away. Some commute all the way to Tromsø, taking the express boat in the morning. Twenty kilometres takes you to the ferry slip, and then it’s an hour by boat to the centre of Tromsø. It’s a spectacular journey: sitting pretty much at sea level makes you feel really in contact with the water while you take in the panoramic views of the mountains and neighbouring communities huddling by the water’s edge. After work, it’s back to the boat, and on days when the boat isn’t running, the commuters work from home. Everyone who works at the school or kindergarten lives here in the village; the same goes for a number of craftsmen and 3 full-time artists. In the old days, though, most of the men here were fishermen, while their wives – ‘fishwives’ – were left at home to look after the house, animals and kids, often for long periods at a time. The fishing industry remains the chosen way of life for several in the village. No wonder then that Northern Norway’s famous poet priest, Petter Dass, wrote around 300 years ago: “Aye, the Fish in the Water, he is our Bread, And if he disappears, we’re closer to Dead!” More about fishing later. Maybe you’d like to try Fish & Chips later? Followed by a tattoo perhaps? No that’s not a new cocktail; Segla Grill & Pub also houses the village’s own professional tattoo studio!

Now we’re standing in front of the heart of the village – our beloved store. Here you can buy yourself something to eat and drink, pick up your parcels, get useful tourist information or simply enjoy pleasant company. There’s a cosy little coffee corner inside with old black-and-white photos of the village. The people who run the shop are the driving force behind the annual raffle that pays for the prolific flowering baskets that adorn the roadside barriers on the hill behind you every summer. But you mustn’t go thinking it was easy-peasy to bring a village shop to Fjordgård. Trade was strictly regulated in the old days. Those who wanted to open a shop had to be granted a concession from the state. And when the first inhabitant of the village became the proud owner of his own plot, the landowner inserted a clause into the sales contract forbidding its use for a store. The landowner was himself a merchant, having his shop miles away, but did not want competition. It wasn’t until 1903 that the village’s first trader was granted the right to set up a so-called ‘country store’. The current store has many similarities with the country stores of old: It’s a family business that has featured several generations behind the counter. And while shops in towns were more specialised, like sports shops and bookstores, country stores were like the forerunners of shopping centres: You could buy everything from reading material to building materials, boat-nails and sweets. Our current shop still sells sweeties, as well as toys and yarn – oh, and windscreen-wash for your car, not to mention anti-slip-coated specialist gloves for working on fishing boats. Gone are the days for measuring: • glass to replace broken windows and • paraffin for your lamps Fruit and veg is all that’s weighed these days – and that you do yourself. What are the opening hours, did you ask? Simple: never closed. Self-service 24/7, 365 days a year. All you need is a bank card to open the door (and pay, of course).

Down by the sea, a little bit further out, we come to the fish dock, which used to be swarming with boats delivering their catch, and the local steamship stopping to deliver goods and post. As far back as the Stone Age, fishing has been the very foundation of life for people in Northern Norway. The Øyfjord was attracting fishermen from distant communities to come and fish for cod. 900 years ago, Norwegians were already exporting cod and herring to England. Dried fish, was sent to Bergen and exported further from there from the 13th century. Then, around 200 years ago, we began salting cod locally and sending it to the ‘Vestlanders’ who made it into what we call ‘klippfisk’. If you’ve ever had the famous dish ‘Bacalao’, then you’ve eaten klippfisk. Fjordgård got its first fish processing plant over 100 years ago. The fishermen themselves moved with the seasons. They fished for ‘skrei’, cod ready for spawning, in Lofoten in January, and fished for spring cod in Finnmark in April. After that, they fished ‘home waters’: pollock in the summer and herring in the autumn. According to a 19th century report, the fishermen were “brave and bold at sea, uncommonly skilled in sailing”. But the sea is a dangerous workplace, and many men lost their lives in attempting to provide for their families. That has happened to us before, in our own lifetime. Wives and children alike knew that it was no means certain that daddy would come home. The women had to learn to manage for weeks at a time on their own, making them independent in a way far different from city women. And when Daddy did come home, maybe there’d be a present from Lofoten or Finnmark for the kids – a new bike, maybe, or a doll’s pram? Many fishermen still work far from home, and it is not unusual to work one month at sea followed by one month at home throughout the year. So it was perhaps a small consolation that fishermen in the past were entitled to a certain amount of sustenance from the boat owner; according to a report from 1769, they had the right to be provides with 37 kilos of bread and, to quote the report, “a little brandy for emergency thirst in evil weather”. Now, the fish processing plant has closed down and the fishermen deliver their catch elsewhere, to Husøy on the other side of the fjord, for example. Life is set to return to the quayside however, in the form of people staying over at the new Segla Summit Hotel. Maybe you’re one of them?

While I continue, stroll along to the next crossroads and stop where a slope climbs steeply upwards. There you’ll see something you’re unlikely to have ever come across before! But a little bit of history first: stone tools which can be up to 4000 years old have been found in Fjordgård and there is proof of permanent settlement here prior to 1500 BCE. Those who formerly lived here, however, did not own their own homes. For several hundred years, so-called ‘oppsitters’ – a bit like tenant crofters – had to pay rent to live in the houses. The owners usually lived far away. Øyfjord ownerships rights were very attractive, not least because all had to pay a so-called ‘rowing out tax’ to the landowner. Originally, the entire west side of the fjord belonged to Øyfjord Farm, which main seat was further out along the fjord, much closer to the rich fishing waters. But it was common to spend the winter months at Øyfjordvær and the summer season on a little farm here in Fjordgård. In this way, Fjordgård became one of the oldest permanent settlements on the fjord. The very first person to buy and own their own home in the village was fisherman Søren Pettersen. He bought the property in 1888. Nowadays – and indeed since the 1930s – everyone owns their own house. Everyone who has ever lived in Fjordgård has had to learn to manage a local phenomenon we call Tuillrossa – our very own storms. When the wind is in from the west, it builds up speed down the Segla ridge and hits the village with such force that everything not tied down is whipped away with it. Even roofs have occasionally ‘gone with the wind’ as Hollywood might express it. One autumn she actually managed to rip off half the eastern wall of the school and chase it off down the hill. No one was injured, fortunately. Look at the little weather-beaten house on the upper side of the road: you’ll see it’s anchored to the ground using guy cable. The houses round about of a less venerable age actually have iron posts built into the walls. Tuillrossa won’t be getting her way here! All this underlines the truth of a 19th century report into the character of the local people: “In reality, they have shown considerable aptitude in their battle for existence. The inhabitants are (…) persistent and thrifty in difficult times”. The people are helpful too. They ring each other to warn their neighbours to get everything indoors because “tuillrossa is on her way tonight”. When rossa has done her worst, certain questions inevitably turn up on Facebook: “Anyone missing a garden chair; it’s down in Chapel Street,” or “If anyone’s seen my pump cover, can you let me know?” So if you’re the kind of person that likes to feel the forces of nature, then you’ve come to the right place!

If we look back down towards the sea again, we can see the 60s and 70s Fjordgård equivalent of the arrivals hall – the steamship quay. Before we got the tunnels, the main way in and out of Fjordgård was by sea ¬– to transport people and goods, to get to church on Sundays and to the churchyard en route to the pearly gates. But then public transport entered the Øyfjord scene in 1908 in the shape of a regular steamship service, if only to Øyfjordvær, further out in the fjord. I guess you’re probably thinking that only the smallest ships served such a thinly populated area? Well, the contrary was true: Because the route was prone to the most severe weather in the entire region, the steamship company employed their largest ships here, such as the D/S Skjervøy, for example. It was 43 metres long, had two hatches, boom, crane and double winches, and a capacity of as many as 150 persons Fjordgård itself became a regular stop some time later, first at the fish dock that we talked about just now. There the water wasn’t deep enough for the ship to dock, so it anchored up at a distance and the ‘post boat’ had to be rowed out to collect both goods and people. The steamship quay you can see today was completed in 1962, allowing larger boats to lay alongside for the first time. Today, the steamship’s days are gone, but the quayside has taken on a new life. Now it boasts an art gallery, where one of the local artists exhibits her work. Like the steamships, the gallery also carries a suggestion of the great wide world, for the artist who owns the gallery has exhibited in New York, China and Germany – and some of her work decorates the walls of the Norwegian Research Station in Antarctica no less. Her motifs preferably stem from local or, indeed, cosmic natural phenomena, and her works include series depicting solar eclipses, the Northern Lights and the passage of Venus. Fancy a look? You can find the artist’s website in the text, and the gallery itself is open through the summer. (Artist’s website: www.jennymariejohnsen.com)

Fjordgård lies below steep mountainsides. If they had been even steeper, the danger of avalanche would actually be eased as the build-up of snow would be rendered impossible. As it is, the mountainside is not quite steep enough to stop the snow collecting, meaning that it can later plummet with deadly force, forming enormous avalanches that mercilessly mow down everything in their path. This has happened to us before. Fjordgård has experience avalanches causing the loss of life and the total destruction of buildings and homes. It is of course for this very reason that the village has now become the scene of tremendous engineering works: just look at the avalanche protection we’ve had built here above the road. 14 metres high and half a kilometre long, it’s what’s known as a gabion wall ¬– one of the largest of its kind in northern Europe. The pathway to getting the construction granted was long and hard. We’ll talk more about that in a bit. Perhaps you’re wondering what it’s actually like to live here in the winter, in what we call ‘mørketida’ – that is to say the time from when the sun disappears beneath the horizon in late autumn and does not return until February. Well, it’s not actually as dark as people tend to think. November days are often lit by a blazing orange and pink sky, while snow introduces an entire palette of blues. And people are quick to light their houses, both inside and out. Since we are so far from any cities or towns, we don’t suffer from light pollution. So in clear weather, there’s always the starry sky, often accompanied by the green and violet dance of Northern Lights in winter. In the winter, the temperature falls to around minus 10 degrees, while in summer well over 20 degrees is not uncommon, especially in July. We do occasionally have what we call ‘tropic nights’ when the temperature doesn’t fall below 20 degrees all night, but that’s something we don’t mind missing out on. What do you think?

Imagine you’re a fisherman who has to get up in the early hours every morning and row out to the fishing fields. That’s what reality was like here for many hundreds of years. People settled around the mouth of the fjord, as close to the fish as possible. Once there were three settlements out there; all have now been abandoned. Øyfjordvær was once the bustling hub of the entire fjord with a fish processing plant, cod liver oil factory, church, post office, telephone, school and store. People who grew up there had to move here to Fjordgård and testify: ‘Now my home lies deserted’. But why, you ask, were these settlements abandoned? The answer lies before you: the sea. Øyfjordvær had no natural harbour in which to bring boats and fish safely to land. To get round the problem, the Norwegian Port Authority built piers along the shore at which boats could land their catch, but these were repeatedly destroyed by winter storms. And then, in 1947, came the coup de grâce for the fjord’s former centre. One spring tide was so powerful it tore away the quayside, boathouses and fishing vessels and smashed them all to pieces. The people had had enough. They headed south. But not very far. The Norwegian parliament provided a special grant so they could move to Husøy, over on the other side, which is currently home to about 300 people, nearly twice as many inhabitants as Fjordgård has. There was no natural harbour here in Fjordgård either, so what was our fate to be? The answer to that comes in the next chapter.

Where we are standing now is the place that decided whether the village of Fjordgård was to live or die. Without safe conditions for the fishing fleet – which provided employment and kept the fish processing plant fed – the future here was unsure. The struggle to solve the problem was taken on by the old Fjordgård Fishing Association back in the 1960s. They thought at the time that it was impossible to create a harbour here: the sea was too deep along the shore. The fishing association thus put out a call for mooring chains anchored in the seabed where the boats could tie up. But alas, the chains proved difficult to maintain and did not provide sufficient protection “when storms were raging and the marine undertow wore and tore at the moorings” as villager Werner Hansen rather poetically phrased it. A number of boats have struggled and sunk over the years, while others have been broken into driftwood against the shore. “Being a fishing village without a safe harbour is a considerable trial for the community out here,” Werner explained. He had now become the driving force behind the construction of a proper harbour. The struggle turned out to be arduous, long and not least dramatic! More about that at our last stop next.

Optimistic fishermen founded the Fjordgård Marina Association in 2006, and dipped deeply into their own pockets to have an expensive zoning plan drawn up, complete with drawings, geological surveys and risk analyses. “If you want to have a harbour,” said the local authority, “then we need to document the risk of avalanche first”. The forthcoming 2010 report was eagerly awaited. Reading it was like a slap in the face. Fjordgård was so prone to avalanche, the report declared, that the place was barely inhabitable. There were a number of rivers that could cause perilous slush flows and the danger of avalanche from the mountains was sufficient to prevent the building of roads, houses and, of course, a harbour. It was as if the experts had daubed a red cross on the entire village. Fishing boats flagged out to neighbouring communities and the fish processing plant – a source of employment for over 100 years – was closed down. So now what? Were the authorities going to offer Fjordgård inhabitants the money to move too? Should our home, too, be abandoned? It was then that the bright sparks in Fjordgård Marina came up with the ingenious idea of how to take out an entire flock of birds with one stone: engineers could take masses of rock out of the hillside and use them to build the new harbour, improve and expand the old avalanche protection and reroute the slush-flow prone rivers, all in one fell swoop! The authorities brought in the experts for the umpteenth time and their verdict was clear: it was perfectly possible. You have seen the new avalanche protection behind you, a number of rivers now enter the fjord north of the village, and the new harbour is right in front of you. Thanks to the years of hard work and dedication of our local heroes, our home is hardly likely to be deserted any time soon. Fjordgård has earned the right to live on. And with that, dear listener, our audioguide comes to an end. Thank you for joining us; we wish you the very best in your onward journey – wherever it may take you.