The role of the Sami Parliament

The Sami Parliament (Sámediggi) is the Sami people's elected parliament in Norway, an independent elected body that identifies and develops its own policies and priorities. The Sami Parliament strengthens the Sami political position, promotes Sami interests in Norway, and contributes to an equal and fair treatment of the Sami people.

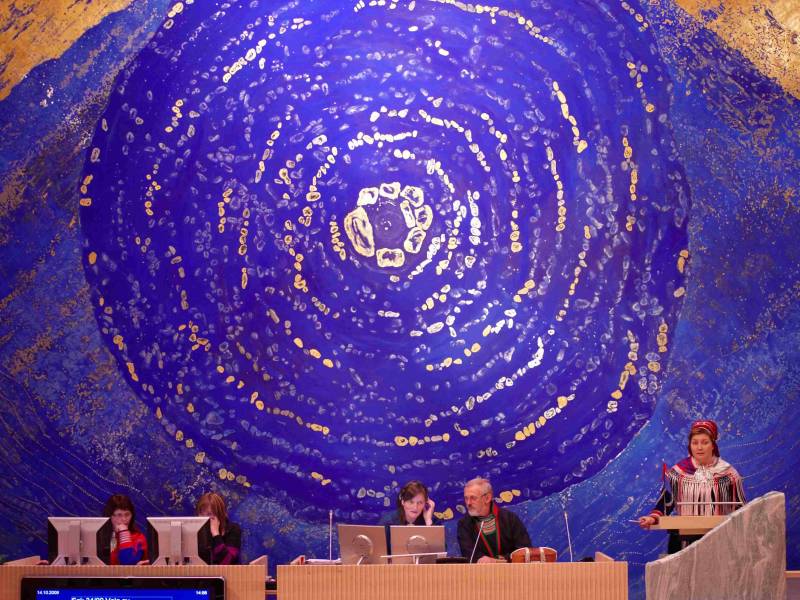

The Sami Parliament is governed under the parliamentary principle, where the sitting Sami Parliament bases its activities on trust in plenary. The Sami Parliament in plenary is the Sami Parliament's highest body and authority.

The Sami Parliament's plenary session determines the Parliament's rules of procedure, with rules and guidelines for all other activities under the auspices of the Sami Parliament. There are usually four committee and plenary meetings a year at the Sami Parliament in Karasjok, and all meetings are open to the public. The plenary meetings are also streamed online.

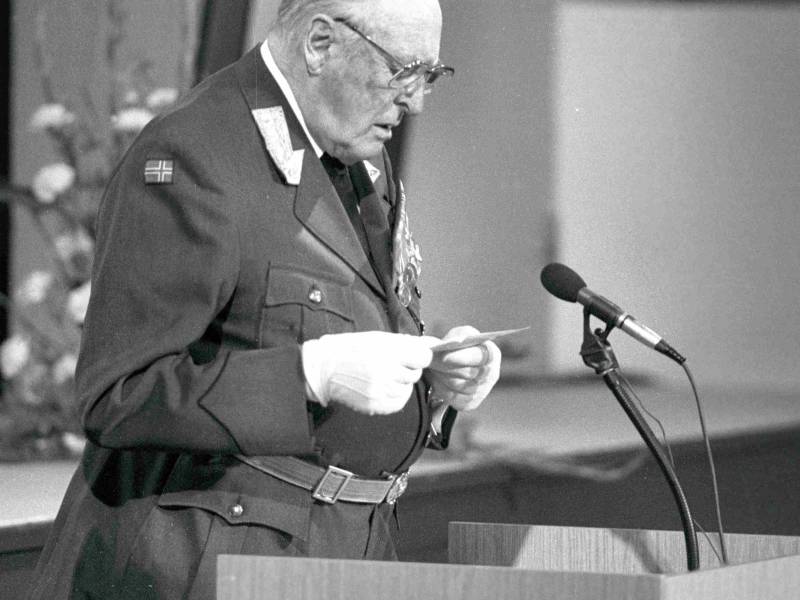

The President of the Sámediggi is elected by the plenum, and he or she appoints his or her council members. The Sámediggi Council functions as the Sámediggi's «government», which governs as long as it has the confidence of the majority of the Sámediggi plenary.

The Sami Parliament is also an administrative body, allocating funds for various Sami businesses, cultural, and linguistic purposes according to its own priorities. The Norwegian government allocates funds annually for Sami causes in the state budget, and the Storting receives the Sami Parliament's annual report.

The main administration for the Sami Parliament is located in Karasjok, but also has offices in Kautokeino, Nesseby, Kåfjord, Tromsø, Skånland, Tysfjord, Hattfjelldal and Snåsa. There are approximately 150 employees in the administration.

The Sami Parliament is the Sami people's voice nationally and internationally, and participates in the UN Permanent Indigenous Forum in New York. The Sami Parliament is also a close partner of the other two Sami parliaments in Finland and Sweden, as well as other Sami organizations in

Russia through the Sami Parliamentary Co-operation Council (SPR). The Sami Parliament also takes part in various working groups in the Barents area and the Arctic.

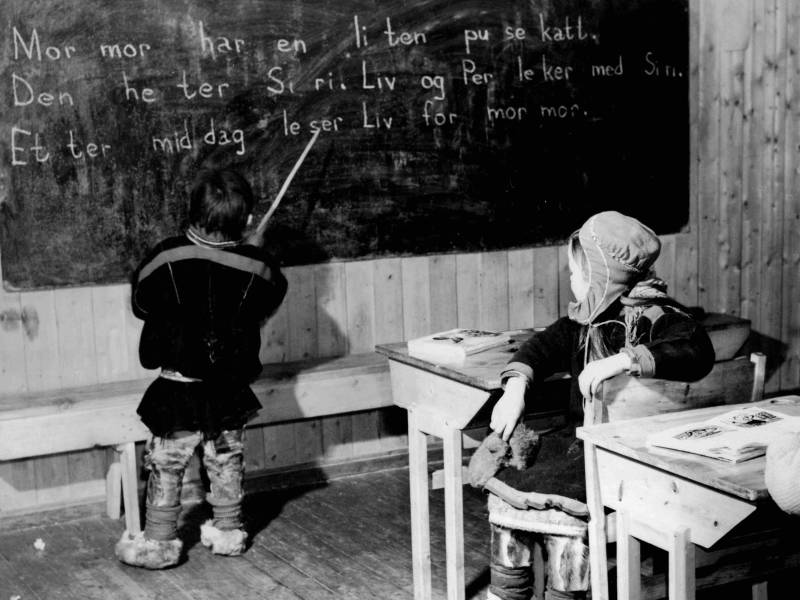

As indigenous peoples in Norway, the Sami have the right to be consulted in matters concerning them. In June 2021, the duty to consult was enacted, which means that the Norwegian authorities are obliged to include Sami people early in decision-making processes. This obligation applies to the state, county, and municipalities.

Read more about the consultation obligation in the link below:

Audio guides available in:Norsk bokmål, English (British)